In The Constitution of Knowledge, Jonathan Rauch defends the epistemic institutions—science, journalism, academia—that uphold truth in democratic societies. He explores how norms like open debate, peer review, and fact-checking serve as a “constitution” governing the marketplace of ideas. Amid rising disinformation and tribal polarization, Rauch argues for preserving this knowledge system through free speech, tolerance, and intellectual humility. Blending political philosophy, history, and media studies, the book is both a defense and a roadmap for safeguarding truth in a digital age. It's an essential read for anyone concerned about democracy, truth, and the future of civil discourse.

About Jonathan Rauch

Jonathan Rauch is an American author, journalist, and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. His work spans politics, public policy, and social issues, with a focus on free speech, liberal democracy, and truth-seeking institutions. In The Constitution of Knowledge, Rauch articulates a defense of the social structures—like journalism and science—that enable societies to reach consensus on truth. He also authored Kindly Inquisitors, a classic work on intellectual freedom. A contributing writer for The Atlantic, Rauch is known for his calm, reasoned voice and for championing civil discourse, open debate, and the value of shared epistemic standards.

Similar Books

Nexus

In a future where mind-enhancing nanotechnology connects brains like apps, a young scientist develops Nexus 5, a powerful upgrade that could revolutionize human evolution—or destroy it. Caught between shadowy government forces and post-human extremists, he must navigate a dangerous world of espionage, ethics, and power struggles. Fast-paced and thought-provoking, Nexus explores the limits of human potential and the morality of scientific progress in a near-future thriller that blends cyberpunk and biotech with philosophical depth.

The Watchman's Rattle: Thinking Our Way Out of Extinction

Rebecca Costa’s The Watchman’s Rattle explores how civilizations collapse when complexity outpaces our ability to solve problems. Blending science, history, and psychology, she argues that as global crises become more complex, society risks paralysis unless we evolve our cognitive strategies. Costa introduces the idea of “cognitive threshold,” suggesting we must adopt new ways of thinking—such as intuition and pattern recognition—to survive modern challenges. The book links ancient failures with contemporary threats like climate change and global instability. It’s a call to embrace adaptive thinking before our most pressing problems become unsolvable.

Bittersweet

by Susan Cain

In Bittersweet, Susan Cain examines the power of embracing sorrow and longing as essential aspects of the human experience. She argues that acknowledging and accepting these emotions can lead to greater creativity, connection, and fulfillment. Drawing on research and personal anecdotes, Cain challenges the cultural emphasis on constant positivity, advocating for a more nuanced understanding of happiness. The book offers a compelling perspective on the value of melancholy and its role in leading a meaningful life.

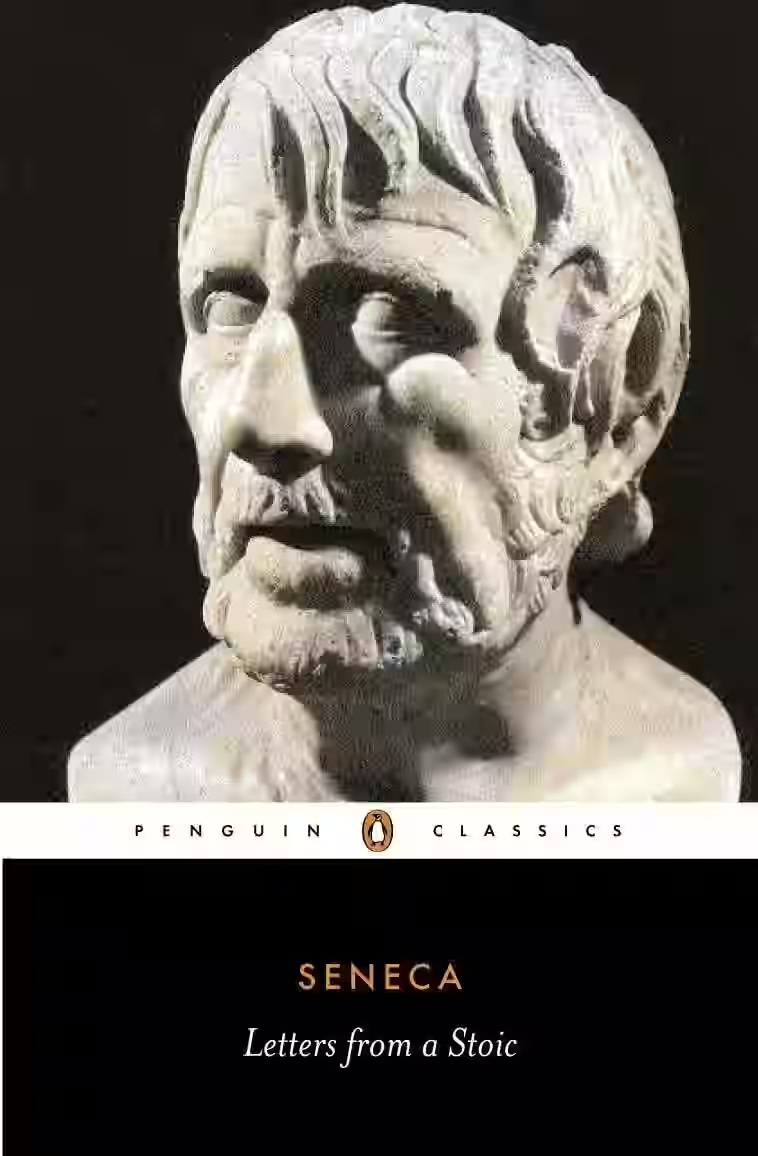

Letters from a Stoic

by Seneca

A cornerstone of Stoic philosophy, Letters from a Stoic is a collection of personal correspondence from the Roman philosopher Seneca to his friend Lucilius. These letters offer timeless wisdom on topics such as grief, wealth, friendship, fear, and the art of living. Seneca advocates for virtue, rationality, and emotional resilience, emphasizing control over one’s inner life regardless of external events. His practical advice and moral reflections are accessible yet profound, making this a foundational text for anyone seeking clarity, discipline, and inner peace. It remains a vital guide for modern readers exploring the philosophy of Stoicism.